‘It prepared me so well’: First graduate of precollege program for Native students reflects on time at UW–Madison

Michael Williams, pictured here in 2017 as a senior at Seymour Community High School, completed a UW–Madison precollege program as a high school student. He credits the program with helping him succeed at UW–Madison. Photo: Bryce Richter

Michael Williams hatched a plan in high school: He’d become an attorney, then use his legal skills to benefit his fellow citizens of the Oneida Nation of Wisconsin.

He’s now a step closer to that goal. Williams, who graduated this spring from UW–Madison, has been accepted to the University of Wisconsin Law School. He’ll begin classes this fall.

“I spent a lot of my time as an undergraduate advocating for Native students and Native issues,” says Williams, who grew up on the Oneida Indian Reservation near Green Bay, Wisconsin. “By attending law school, I can take my advocacy to the next level. I really want to work with my tribe on federal Indian policy and law.”

Michael Williams became heavily involved in campus life as a UW–Madison undergraduate, including serving as president of Wunk Sheek, an organization for Indigenous students. Submitted photo

Williams credits Information Technology Academy (ITA), a UW–Madison college preparatory program, with helping him get to this point. ITA works with high school students to increase the enrollment rates of diverse students at UW–Madison. It focuses on academic preparation, leadership skills and technology literacy.

ITA has been around for more than two decades, initially serving only the Madison community. Its outreach specifically to American Indian high school students became more deliberate in 2014 when it partnered with the Oneida Nation and the Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians.

Williams was a sophomore at Seymour Community High School in 2014 when he was selected to be in the first cohort of ITA students from the Oneida and Lac du Flambeau communities. He now has the distinction of being the first student from that first cohort to graduate from UW–Madison. He earned a bachelor’s degree this spring in psychology with a certificate in American Indian studies.

“ITA prepared me so well for college,” Williams says. “It taught me so much — how to follow deadlines, how to study, how to budget my time, how to communicate with professors. It also provided me with a community of unconditional support on campus.”

Students like Williams who complete the ITA program in high school and are accepted to UW–Madison receive full-tuition scholarships for four years and become scholars in the university’s PEOPLE initiative.

Right away, Williams threw himself into multiple academic and leadership opportunities at UW–Madison. He remembers early on asking one of his ITA mentors: “Is there a group on campus for Indigenous students? If not, I’m going to start one.”

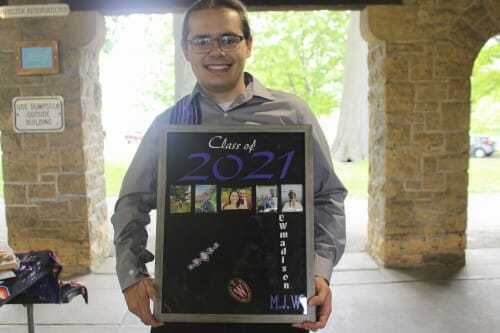

Michael Williams, a member of the first cohort of high school students in a UW–Madison precollege program for Indigenous students, graduated this past May from the university. He’ll be attending UW Law School this fall. Submitted photo

There was one — Wunk Sheek — and Williams joined it his first semester. By the following semester, he was one of the group’s four co-presidents, tasked with planning the group’s spring pow-wow. He stayed heavily involved with Wunk Sheek all four years, serving as president this past year.

“I loved all of the work I did with Wunk Sheek,” he says. “It was very empowering as a student to be given so much responsibility in an organization that I felt so passionate about.”

Williams also participated in the Undergraduate Research Scholars Program, served as an undergraduate representative on the university’s Sustainability Advisory Council, and helped revive the MadTown Singers, an Indigenous singing and drumming group.

The group performed before 1,000 people on campus in September of 2019 at an event that kicked off a celebration of the new Our Shared Future marker on Bascom Hill. The marker recognizes the land as the ancestral home of the Ho-Chunk people. In an 1832 treaty, the Ho-Chunk Nation was forced to cede the territory, a place they call Teejop (Dejope, or Four Lakes).

“I think the marker has started meaningful conversations around Indigenous issues on campus,” Williams says. “But the marker is just a start. It needs to be an ongoing conversation of how we can respect this land as the ancestral homelands of the Ho-Chunk Nation.”

Williams also worked all four of his undergraduate years as a part-time employee of ITA, helping to develop and teach technology curriculum to high school students in the program.

“Michael has been a phenomenal asset to UW–Madison during his time here,” says Ron Jetty, ITA’s executive director. “We’re so proud of everything he’s achieved and everything he’s contributed to campus. He’s been a great ambassador for ITA and a prime example of the value of the program.”

Since the ITA Oneida and ITA Lac du Flambeau components were added in 2014, 68 high school students from the two communities have completed the preparatory program. All of those students were accepted to an institution of higher learning, with 30 of them deciding to attend UW–Madison. The goal of ITA is to prepare its students to be competitive in the college applications process or in a career field, regardless of whether they choose to attend college or are admitted to UW–Madison or another institution.

“We are proud of all of our graduates and especially proud of those who choose to attend UW–Madison,” Jetty says. “The ITA programs are definitely making a major contribution to UW–Madison’s Native student population.”

Williams describes his experience at UW–Madison as largely favorable, with some reservations.

“So much of my time on campus was overwhelmingly positive,” he says. “I got to meet amazing students, faculty and staff members. I got to work on Native projects with Native professors. I got to organize events for Native students, funded by the administration. I don’t take any of that for granted.”

Yet there were times, he says, when he felt his voice and the voices of other Indigenous students were discounted or not taken seriously.

“I spent four years trying to better the Native experience on campus, so it’s important that I call out those negatives,” he says. “In general, what the university can do is listen better to Native students and treat us as scholars with valuable expertise to share. University administrators say they want to hear the Native voice, yet we often meet resistance when we offer it.”

Williams says he intends to remain part of the conversation on Native issues as a law student on campus, in hopes of continuing to improve the experience at UW–Madison for Indigenous students.

Tags: diversity, Native Nations, student life