Trying to predict whether 19-year-old Zack Wisniewski would show up to court-ordered appointments when he was released from jail before trial was a bit like trying to guess next month’s weather — even for Zack himself.

He was staying with friends in Stoughton, didn’t have a car to get to court-ordered drug tests in Madison, and had to call in daily to find out which days he’d need to go in. And he was still using and selling prescription drugs and marijuana.

“I had no way of knowing if I was going to miss court because of a ride or … who knows what was going to happen … if I was just gonna be stupid and skip out,” Wisniewski said.

He’d get out on cash bail or signature bonds, signed agreements in which defendants promise to show up for court and follow court-imposed “conditions of release,” or pay money if they don’t. But again and again, he’d return to jail after missing an appointment or getting caught with drugs.

Defendants like Wisniewski pay a steep cost for these violations in Wisconsin, one of eight states where a defendant doesn’t have to intentionally skip court to be criminally charged with “bail jumping.” Here, violating any condition of release can count as a new crime — even when the action in question, such as drinking or breaking curfew, isn’t itself a crime — and it now tops the list of the state’s most common charges. In some cases, a person can be charged with multiple counts of bail jumping for a single incident, sometimes leading to decades of potential prison time and, according to some defense attorneys and judges, a pressure to plead guilty.

Zack Wisniewski in the kitchen at Just Bakery in Madison, on Wednesday, February 19, 2020. Photo by Michelle Stocker

Over the past 20 years, even as numbers for other common charges fell, bail jumping charges have surged in Wisconsin, according to a Wisconsin Law Review analysis, which found the crime was the state’s top charge in 2016.

Wisniewski said he racked up around nine bail jumping charges, though several were later dropped.

He isn’t alone. Nearly everyone he met in jail had also been charged with bail jumping, he said, representing just a fraction of the tens of thousands of bail jumping charges filed across the state each year.

It is not clear how Wisconsin got here. Prosecutors, judges, defense attorneys and legislators offer conflicting explanations for the spike, alternately pointing to a pivotal Wisconsin Supreme Court case, a powerful mathematical formula or a massive cultural shift.

And as the state considers releasing more people on bond, the number of bail jumping charges could rise further.

Meanwhile, key players in the justice system are seeking to reverse the tide. They are calling for a rethinking of the rules defendants must follow and the consequences they face if they break them, arguing that strict conditions and harsh penalties might not be the best way to protect communities and ensure defendants show up for court.

Bail jumping basics

Some people facing criminal charges are considered so dangerous that a judge orders them to await trial in jail. But in the vast majority of cases, a judge will allow the person to return to the community while the case is pending, and he or she is typically given rules to obey while awaiting trial.

Wisconsin law authorizes courts to impose bond conditions to protect community members “from serious bodily harm” and to prevent witness intimidation.

Prosecutors recommend conditions, defense attorneys argue for less restrictive conditions, and the judge or court commissioner decides.

Some conditions are prohibitions: no alcohol, for example, or no contact with a co-defendant or victim. Others are obligations: wear a GPS monitor or electronic alcohol monitor, take drug tests, check in weekly with a court officer or obey a curfew.

If the carrot is freedom, the stick is criminal bail jumping charges; each violation is a separate criminal charge. If the defendant is on bail for a misdemeanor, each violation is a misdemeanor, punishable by up to nine months in jail. But if the defendant is on bail for a felony, that same violation would be charged as a felony, punishable by up to six years in prison. For example, if a person who is on bail for simple battery, a misdemeanor, drinks in violation of a court order, they would face misdemeanor bail jumping charges, but a person on bail for substantial battery, a felony, would face felony bail jumping charges for that same violation.

Zack Wisniewski prepares to teach a food safety class at Just Bakery, the same employment training program that helped him find stability after he racked up several bail jumping charges.

Prosecutors have sole discretion over how many charges, if any, to file.

While Wisniewski points to his own addiction as the biggest reason for his legal problems, he thinks he might not have racked up so many charges if someone had offered more help with things like housing and transportation.

Each time he’d get out again, he’d hear the same things at his bail monitoring appointments. “They were just like, ‘You need to cut the drugs, you need to stop smoking,” Wisniewski said, though he said he wasn’t offered drug treatment until he was later transferred to drug court.

“They were always just like, ‘Well, are you going to get the help?’ And I’m like, ‘Well yeah, but I don't know how. I don’t know where to start,’” Wisniewski said. “They expect you to be able to do it all on your own.

“We’re dealing with someone who doesn’t have the ability to process their own decision-making,” he said. “Especially if they’re on drugs, they can’t make the right decisions.”

Rebecca Trolinger is a social worker with Dane County Pretrial Services, the new incarnation of the bail monitoring program Wisniewski participated in, which is available to defendants when ordered by the court.

The program is geared toward ensuring defendants comply with their conditions of release and takes a social work approach, Trolinger said. Social workers maintain bulletin boards of community resources to help defendants access employment, housing, drug treatment, food, health care or transportation, and they’ll contact those other community organizations on a defendant’s behalf if the defendant gives them permission.

“We advocate and work with people to the best of our abilities,” Trolinger said.

But because her office can’t pay for those services itself, defendants seeking housing might spend months on a waitlist, and those seeking drug treatment might need to apply for insurance or vie for a limited number of county-funded spots.

And, she said, those dealing with homelessness, poverty or addiction have a lot on their plates.

“Some of these issues certainly coexist and can make a person’s ability to access or even follow through with things a little bit more difficult,” Trolinger said.

Trolinger said her office is currently working to improve communications with outside to improve communications with outside agencies to make referrals smoother for her clients.

Releasing defendants without offering support sets them up for failure — and bail jumping charges, Wisniewski said.

It’s “like a little extra leash. Here's a little freedom — see how you do,” Wisniewski said. “But they know we're gonna bite our own legs off and try to escape.”

The Pretrial Services office’s software does not track how often clients receive bail jumping charges.

In Wisniewski’s case, he ran out of chances. In his words, he “failed” bail monitoring and then “failed” drug court, earning enough bail jumping charges that the court eventually refused to release him.

In jail, he said, he found the help he wishes he’d found before. His cellmate told him about Just Bakery’s employment training program, which offered not just job training but case management and help finding housing. Through the jail’s work-release program, he spent six months in training at the bakery.

Wisniewski ultimately pleaded guilty to two counts of felony bail jumping, along with two drug charges. Pleading to the bail jumping charges, he said, was the only way to avoid a prison sentence. He was sentenced to three years of probation and time served.

Today, Wisniewski works as an assistant instructor at Just Bakery, teaching students not so different from his 2017 self.

Today, Wisniewski works as an assistant instructor at Just Bakery, teaching students not so different from his 2017 self.

Seeing a spike

Michele LaVigne, director of the Public Defender Project at UW Law School has observed the upswing in bail jumping charges for years. She was called upon by the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers to create a guide to help Wisconsin defense attorneys understand bail processes, and in 2018, she shared what she knew with the Wisconsin Legislative Council Study Committee on Bail and Pretrial Conditions.

“I think one of the things that floored them was there's no data,” LaVigne said.

Enter Amy Johnson, a student of LaVigne’s who had spent three decades in the information technology field before enrolling in law school.

Johnson had read a legal opinion warning that Wisconsin defendants could face bail jumping sentences longer than those for their original charges.

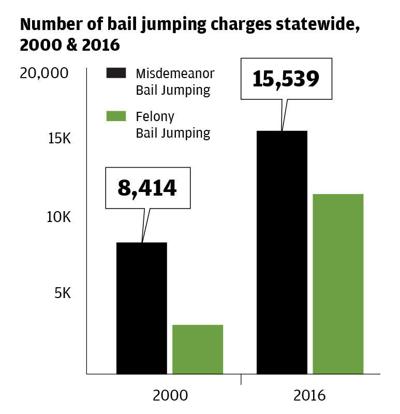

Analyzing data from the Wisconsin Circuit Court Access database, Johnson found that bail jumping charges had spiked statewide even as numbers for seven of the eight other most common charges fell.

From 2000 to 2016, misdemeanor bail jumping went from being the state’s fifth most charged crime to the second, and felony bail jumping shot from 10th place to third.

By 2016, “bail jumping (in total) was the number one charge in Wisconsin, ahead of disorderly conduct by over 5,000 charges,” Johnson wrote.

Amy Johnson, an IT professional turned law student, compiled and analyzed data on fully adjudicated Wisconsin Circuit Court cases for the years 2000 to 2016. The Wisconsin courts system does not track the number of bail jumping charges filed, so Johnson's analysis has provided key insight.

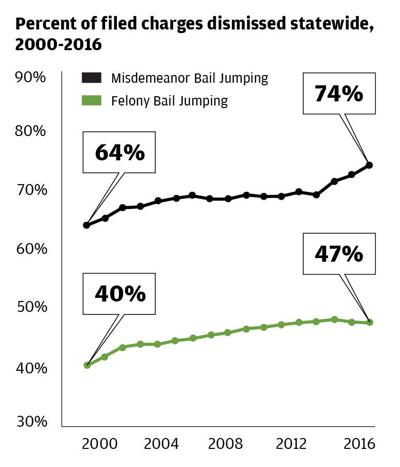

Examining data for seven Wisconsin counties, Johnson found that in all but one, more than 60% of the bail jumping charges were dismissed. In two of those counties — Iowa and Chippewa — 90% were dismissed.

Defense attorneys argue that when prosecutors bring charges and later dismiss them, it’s because they are using the charges as leverage to pressure defendants to plead guilty. In other cases, defendants might plead to bail jumping while the original charge is dismissed.

“Lawyers can say, ‘I know they're doing this,’” LaVigne said. “But sometimes data speaks louder. And that data just screams.”

Protecting communities?

Chippewa County District Attorney Wade C. Newell doesn’t see a problem. As a prosecutor, he’s the one who requests bail conditions. The conditions are designed to keep the community safe, he said, and bail jumping charges are the force behind those conditions.

The conditions he requests, such as requiring no contact with a victim or avoiding alcohol, could help prevent another similar crime — and they might help defendants too, he said.

“It's just kind of like when your parents gave you rules at home and told you to be home by 10 o'clock,” Newell said. “It wasn't because they thought that you were going to do something criminally wrong every time it was 10:05. They just knew that it was less likely you would get into trouble if you weren't out late at night.”

Meanwhile, some question whether bail conditions actually work as intended. Former Wisconsin Court of Appeals Judge Paul Higginbotham said because so many defendants are dealing with substance abuse or mental health problems that can make compliance difficult, the conditions are often a recipe for new charges.

“If … you impose a condition that the odds of this person not being able to comply are very high, then why are you doing that?” Higginbotham asks. “Where’s the justice in that?”

He’d like to see courts use risk assessment tools to identify defendants who might benefit from a “treatment alternative” that could help ensure they won’t violate their bail conditions.

“If that’s not in place, then these folks are being set up for failure, and then they find themselves back in jail,” Higginbotham said. “And this is why the jails are overcrowded.”

When a violation is not violent, not connected to the victim or the underlying charge and not fleeing justice, Higginbotham believes courts should respond using other tools at their disposal instead of new charges.

If the defendant was out without bail, courts could require he remain detained unless he pays money bail, Higginbotham said, and if the defendant was out on money bail, courts could require the defendant to forfeit that bail. And courts could consider bail jumping at sentencing even if it’s not a new charge.

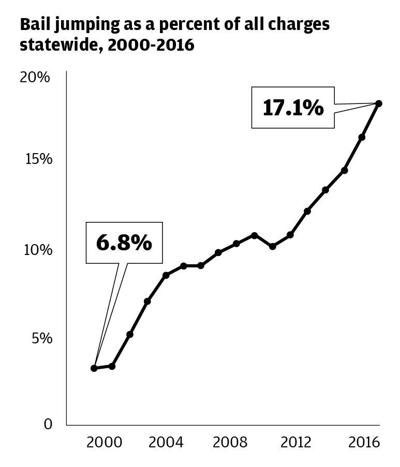

According to Amy Johnson's analysis for a 2018 Wisconsin Law Review article, bail jumping charges makes up a growing share of all criminal charges filed in the state.

Others, like Wisconsin State Rep. David Crowley, D-Milwaukee, say it’s inherently wrong to try to control the behavior of a person who is still presumed innocent.

“I haven't even been found guilty yet, so to say that I need a behavior modification — I think it's a little disingenuous,” Crowley said.

In December, Crowley and Sen. LaTonya Johnson, D-Milwaukee introduced Assembly Bill 638, which would narrow the definition of bail jumping so that it’s only a crime if the defendant intentionally fails to appear in court, goes to a place from which he has been barred, or makes contact with someone the court has ordered him not to.

The bill would also make all bail jumping charges misdemeanors rather than felonies, lower the maximum sentence for the misdemeanor from nine months to 90 days, and allow for only one bail jumping charge for each original charge.

Rep. Shae Sortwell, R-Two Rivers, is the bill’s only Republican sponsor. For him, the issue is personal. A friend from his Army days was charged with selling heroin, released on bond, and then overdosed. The police came and revived the friend, but he was charged with felony bail jumping for having drugs, in violation of his bail conditions. While his original charge was later reduced, he became a felon due to the bail jumping charges, a consequence Sortwell considers disproportionate.

“The thing he was guilty of, more than anything, is being a moron,” Sortwell said. “He was guilty of being ... an addict.”

Going overboard?

UW’s LaVigne believes bail conditions are a reasonable way to try to protect the community. But, she said, “we go overboard on it.” In many Wisconsin counties, LaVigne argues, those conditions have grown more numerous and punitive thanks to a “more-is-better philosophy.”

La Crosse County Circuit Court Judge Elliott Levine agrees, noting that every bond includes a prohibition on committing a new crime, meaning that any new crime results in both a charge for that crime and a bail jumping charge. “Why they wrote that in there is sort of beyond me, because you're essentially doubling up the crime,” Levine said.

Cecelia Klingele, a professor at the UW Law School, said the rules and penalties may not match the alleged crimes.

“We have to remember, our system isn't made up primarily of highly dangerous criminals. It's made up mostly of low-level misdemeanants who are engaging in problematic but generally nonviolent behavior,” Klingele said.

Bail jumping charges in Wisconsin are getting dismissed at a higher rate than they were in the past, according to an analysis published in the Wisconsin Law Review, prompting some to say prosecutors are filing the charges in bad faith.

For low-risk defendants, setting restrictive conditions can backfire, even increasing their risk of committing crimes, according to multiple studies analyzed by two University of Cincinnati researchers.

Some defendants are assigned to check in with a pretrial services officer, but may struggle to find transportation or to fit appointments into their work or child care schedules.

Meanwhile, technologies like remote alcohol monitors and GPS devices have given courts new ways to check for compliance with prohibitions on drinking, drug use or location, increasing the likelihood that a person will be charged with bail jumping. In some counties, the defendant must pay for this monitoring.

“Technology is a mixed bag,” Klingele said. It can make the justice system more efficient, “but technologies malfunction and sometimes they allow us to detect behaviors that may have gone unnoticed in the past because they really don't present any danger to the public.”

Higginbotham argues that conditions have “gotten out of control,” with courts sometimes imposing rules that fall outside of the legal parameters. He said conditions should be “narrowly tailored to this particular individual and to the crime that is alleged,” but dockets of 50 to 100 hearings a day can make that a tough ask for judges and court commissioners.

“In many instances ... it almost becomes rote,” said Higginbotham, who believes the Wisconsin Supreme Court should weigh in on this issue to clarify the kinds of conditions courts can set.

Piling on the charges?

Defendants subject to multiple conditions can end up facing multiple bail jumping charges. For example, the drunk dial: A defendant who’s been ordered not to drink or contact his girlfriend gets drunk and calls her, resulting in two new charges.

In the 1998 case State v. Anderson, the Wisconsin Supreme Court found this practice of multiple charging permissible.

Then-Justice Janine Geske opposed the decision.

“The real issue we face in this case is whether the legislature intended, when it created the bail jumping statute in 1969 … to subject the defendant to potentially unlimited criminal charges for violating multiple conditions of one or more bail bonds,” Geske wrote.

To demonstrate the potential consequences of the practice, she cited the hypothetical case of John Riley, “a mentally disabled, alcoholic street person … charged with three counts of shoplifting three bags of potato chips from a drug store on separate days.”

Riley was ordered to live with his mother, see his mental health counselor daily, stay off the drug store’s block, not drink alcohol, and not make contact with a certain friend, Geske wrote. “On one particular day, Mr. Riley starts to drink and then violates the other four conditions.”

According to the majority decision, Riley could face 15 bail jumping charges with a possible jail sentence of more than 11 years and a fine of up to $150,000 — even if he were acquitted of the original charges at trial. Geske found that sentence excessive.

LaVigne believes that court decision prompted prosecutors to “load up” on bail jumping charges. “Over time, they discover the power of this thing,” LaVigne said.

Similarly, the Wisconsin Court of Appeals’ 2008 ruling in State v. Eaglefeathers determined that if a defendant is facing charges in multiple cases, prosecutors can issue multiple bail jumping charges for a single violation.

Johnson’s study of court records found that the number of cases with five or more bail jumping charges grew from 133 in 2000 to 559 in 2016 — an increase of more than 320 percent. Ten Wisconsin counties had at least one case with more than 18 bail jumping counts, she found, and one Kenosha County case had 44 counts.

Former Wisconsin Court of Appeals Judge Paul Higginbotham would like to see the Wisconsin Supreme Court weigh in on what kinds of bail conditions courts can set.

Pressure to plea?

While Johnson notes her study is “not conclusive as to causation,” she observes that, from 2000 to 2016, bail jumping charges were frequently dismissed when a defendant pleaded to another charge and seldom dismissed without.

“It seems Wisconsin’s bail jumping statute and its interpretation by the Wisconsin courts work to provide leverage that prosecutors can use to induce pleas,” Johnson wrote.

Plea deals are routine in U.S. criminal cases today; according to a 2019 report from the Pew Research Center, only 2% of criminal defendants ever go to trial.

If pleas are the goal, these charges are uniquely powerful, as it’s often easy to prove that a person violated their bail conditions. “There's no greater plea extractor than bail jumping charges,” LaVigne said.

Newell acknowledges that a bail jumping charge can “tip the scale” toward a guilty plea, but he said that’s not the goal. The goal, he said, is that the defendant “stop that behavior that makes them a danger.”

And, in the case of defendants who skip court and attempt to evade justice — which, depending on the delay involved, can make it harder for prosecutors to present witnesses — Newell said bail jumping charges are the only way to maintain accountability.

But Rep. Sortwell argues that inducing pleas bypasses the Constitution’s guarantee that defendants will be presumed innocent until proven guilty. “We’ve kind of circumvented the entire idea of the American justice system,” Sortwell said.

Cecelia Klingele, a professor at the UW Law School, says some bail rules and penalties might be unnecessary. “We have to remember, our system is … made up mostly of low-level misdemeanants who are engaging in problematic but generally nonviolent behavior,” Klingele says.

Why the rise?

It’s hard to point to just one cause of the spike in bail jumping charges. There are the court cases setting precedents, as well as stepped-up monitoring.

Courts also impose more numerous bail conditions than they did in the past, said Hank Schultz, a private defense attorney in Crandon, pointing to additional conditions requiring drug or alcohol testing or requiring a defendant to look for work.

And changes in drug preferences have played a role, said Tyler Wickman, a private defense attorney based in Ashland. As drug cases have shifted from marijuana to the more addictive methamphetamine and heroin, defendants are less willing or able to maintain sobriety, Wickman said.

But Milwaukee County District Attorney John Chisholm has his own theory. He points to multiple incentives that could encourage prosecutors to file as many bail jumping charges as possible, including a state staffing formula he considers problematic.

District attorneys’ offices must submit an annual workload report to the Department of Administration documenting the charges they have filed. The state assigns a set number of attorney hours to each type of charge and uses that number to determine how many assistant district attorney positions should be allocated to each county.

Chisholm said felony bail jumping charges, which can be filed in about two hours, count the same as “really serious” felony charges, which can take much longer to craft.

“It is a horrible idea,” Chisholm said.

He’s not the only one worried. A 2007 Legislative Audit Bureau report noted prosecutors had expressed “a number of concerns” with the formula, stating that it “may overstate staffing requirements for counties with high percentages of bail jumping cases.”

Last September, Gov. Tony Evers announced more than 60 new assistant district attorney positions. According to a memo, the Department of Administration had recommended the new positions, and their allocation, based in part on the workload formula.

The formula might help explain why Wisconsin prosecutors opened more than twice as many felony bail jumping cases in 2018 as they did in 2011, and why, as Klingele puts it, “bail jumping is not only the most charged crime, but it’s the most dismissed crime.”

If lawmakers realized what was fueling the increase in bail jumping, Klingele said, they might be tempted to change the formula.

Until they do, the pattern will likely continue.

“There's a rational and justifiable reason why you might see a lot of bail jumping counts on some cases,” Chisholm said. “I don't think it's a good practice, but just based on the way things are structured sometimes it's almost a survival mechanism for some counties.”

Former Judge Higginbotham would like to see courts, prosecutors, defense attorneys, social workers and mental health and substance abuse treatment professionals come together to rework the system for setting conditions and assessing risk — with state and county funding.

“You gotta bring all of these people together and hammer this out so that it works. And I’m not saying that’s easy. That’s complicated. But I think to have a system that both protects public safety and is fair to the defendant, I think that’s what’s required,” he said.

Levine, the La Crosse County judge, said another possible solution is to “quite literally get rid of the crime of bail jumping altogether.”

But according to Newell, the problem is the defendants.

“I think personal accountability has gone down in general,” Newell said. “When a judge told you to do something 20 years ago, you listened to him and you didn't do it because you didn't want to get in any more trouble. I think now ... there's more people doing what they want to do as opposed to what they're told to do.”

Wisconsin State Rep. David Crowley has introduced legislation to narrow the definition of bail jumping, reduce penalties and cap the number of charges. The bill is stalled in committee.

Looking forward

At the Capitol, the bill to narrow the definition of bail jumping and reduce the penalties is waiting in committee. Rep. Sortwell knows it will be hard to rally enough support from his fellow Republicans.

“It’s an uphill battle,” he said. “There’s a few Republicans that really do understand that this is the direction that we need to be going in general with criminal justice reform,” but the divided state government has led to “a silly game” in which neither party wants to give “a win” to the other.

“I was kind of hoping that this is kind of a bipartisan thing across the country and maybe we could see that happen here,” Sortwell said. “Maybe in the next session.”

Indeed, the tides seem to be flowing in the other direction. Earlier this month, the Assembly passed AB 817 which would prohibit courts from releasing any defendant charged with bail jumping for failure to appear unless the defendant pays money bail. A similar bill is now working its way through the Senate.

Back at the bakery, Wisniewski, now 22, said he hopes to one day open his own rehabilitation program, maybe one where participants use video games to distract them from drugs — it’s what worked for him.

He’d like to keep lending the kind of peer support he found, and now gives, at Just Bakery. He thinks people on bail could use more of that.

At bail monitoring appointments, Wisniewski said, “I felt like I was being told by people who had just studied what to tell me,” but the people he met at the bakery had lived it too. “They were telling me like, ‘I've been down your road. Look where I'm at now. Look what I can do.’”

Had he found that kind of support sooner, he might have a couple fewer charges on his record. But sitting in the small classroom filled with the smell of baking cookies, he’s focused on how far he’s come.

“I mean, look where I'm at now,” Wisniewski said. “A complete 180, honestly, from where I was.”