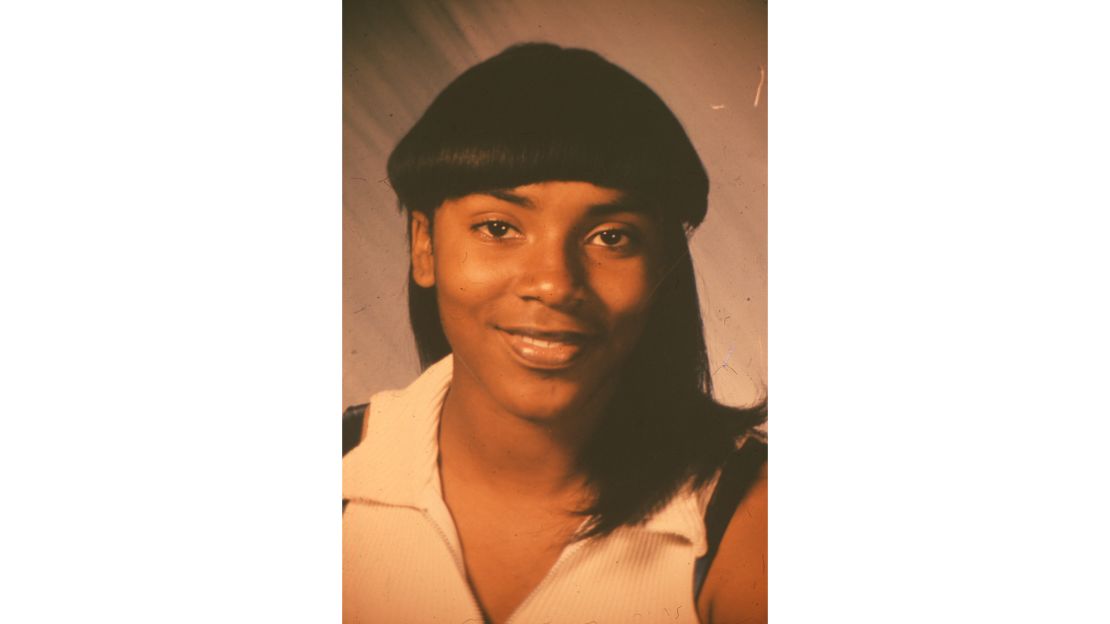

The birth of a child. There’s nothing quite like it.

Especially when your baby is delivered in the middle of the night on the floorboard of your car while you’re speeding down California’s 580 freeway.

That’s how January 24, 1981, began for Donald Lacy. The Bay Area actor and activist wasn’t expecting his first child for at least another three weeks, but as he drove in those early morning hours, his girlfriend made it clear this baby was not about to wait.

Watch 'The Redemption Project with Van Jones'

Soon enough, Lacy was steering the car with one hand as he helped coax their baby girl into the world with the other.

“Her mother … picked her up,” Lacy remembers, “and I was spellbound. She was just beautiful.”

Her name became LoEshé, a combination of two words from Nigerian dialects that in English mean “to love” and “life.”

And her name, Lacy said, could not have suited her better. “She was all of those things. … She was so eager for life that she dove onto the floor of the car.”

But LoEshé wouldn’t live to see 17.

In 1997, there were nearly 100 homicides in LoEshé’s hometown of Oakland, California.

Two of those killings would devastate her family. And one of them would lead her father to search for solace not in America’s courts, but through an alternative method that’s being used in and outside of America’s prisons: restorative justice.

Back in the summer of 1997, Lacy didn’t yet know he’d experience such a process firsthand. What he did know is that his 16-year-old daughter was usually bubbly and upbeat – and that on this August day, something was wrong.

Lacy had returned to Oakland after working in Los Angeles to find LoEshé distraught. He learned that a friend of hers had been killed, and she wanted to do something about it.

Revenge wasn’t what she had in mind. Instead, she wanted her dad’s help writing a play to spread a message of non-violence.

“I remember I was just so proud of her,” Lacy said, “(for) wanting to take her grief and do something positive.”

A few months later, Lacy was back in LA when his pager lit up: “911, 911.”

He called home. There had been another shooting.

Another friend of LoEshé’s was involved.

Except this time, her friend was her killer.

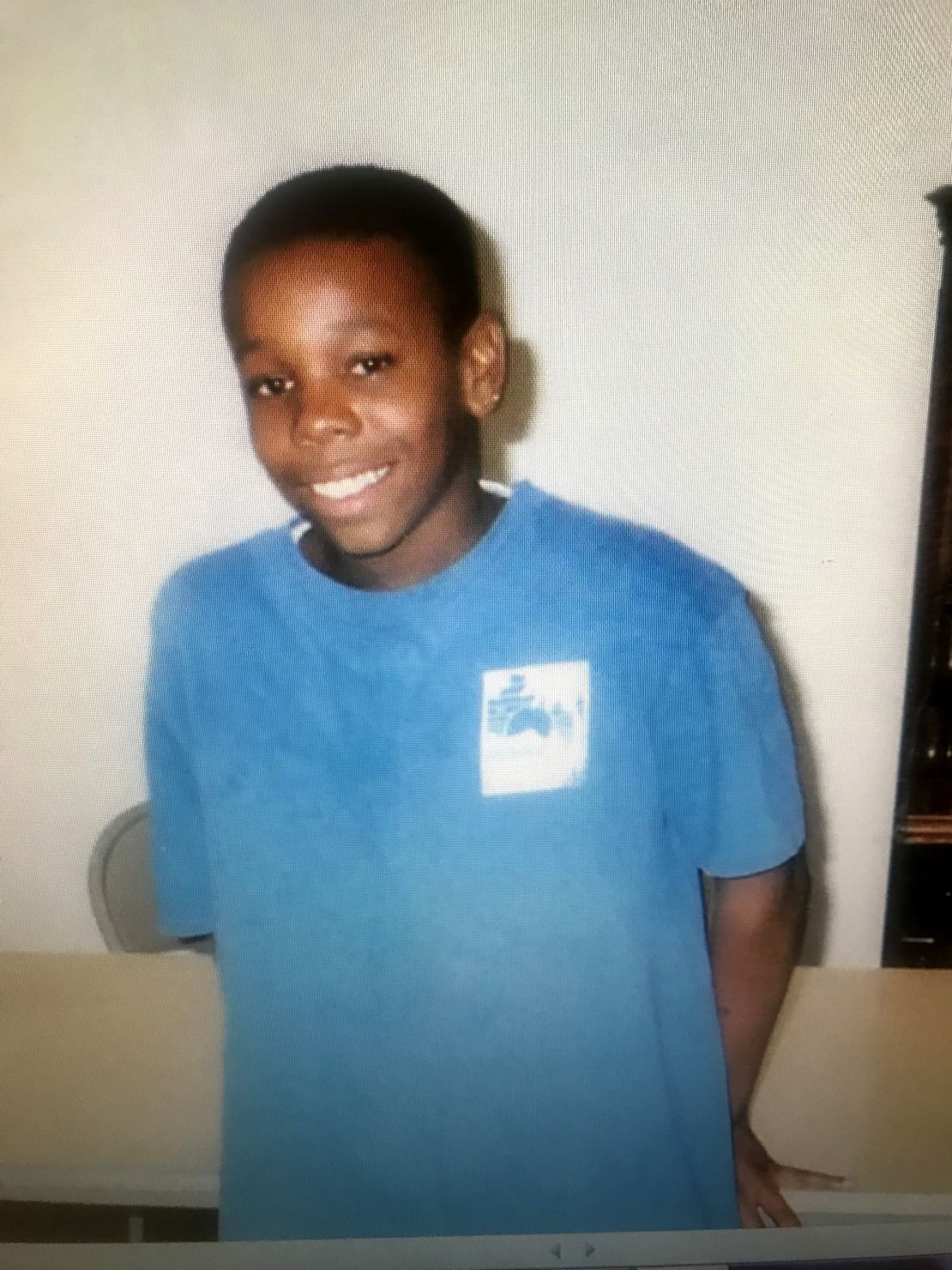

To Christopher Smith, there never seems to be enough time in the day.

The 37-year-old works full-time as a stocker at an equipment supply company while also carrying a full college course load.

But he insists he isn’t complaining. For most of his life, all he’s had is time.

In 2018, Smith was released from prison after spending nearly 21 years there for the murder of LoEshé Lacy.

Smith knew the 16-year-old well. He, too, grew up in Oakland, the oldest of his mother’s five boys. When he and LoEshé were kids, he’d go over to her house to play.

But from the start, Smith had a very different upbringing.

“As early as I can remember, it was a dysfunctional family and unstable household. That was my world,” Smith said. “Every time I woke up in the morning, every time I went outside, that’s what I was consumed with – the dysfunction in my family.”

He says he and his siblings were often left to fend for themselves. When his parents split up, Smith moved from the homes of cousins and friends into foster care, where he says he continued to experience abuse and neglect. He was 13 when he was convicted of his first crime – theft – and after serving a few weeks at juvenile hall, Smith learned his foster mother had told his public defender that she wouldn’t take him back.

For Smith, the rejection was too much for his adolescent mind to comprehend.

“I broke,” he said. “It was like my world just caved in on me. At that point, I had given up completely on everything.”

Smith became a part of Oakland’s “Ghost Town” gang as he cycled in and out of group homes, sometimes running away for weeks at a time to join his fellow gang members. That’s where he was on October 20, 1997.

Smith says there had been a lot of shootings back and forth between rival gangs. And on that Monday, Smith got a call that one of his best friends had been shot. Up to that point, Smith had stood on the sidelines of the gang wars. Now all eyes were on him.

“I went into a panic,” Smith said. “Everyone was kind of looking at me, like, ‘You’re riding around, you’re hanging out with us, you’re here … but what you gonna do?’ … This was my thinking at the time, that If I go and kill someone for my gang, then I would be accepted into a whole other family. A family that will love me, a family that will care for me, a family that will never leave me.”

That night, he and three other Ghost Town members drove the streets of west Oakland. Smith says they were essentially on a hunt, searching for rival gang members to shoot and kill.

They spotted a tan 1975 Dodge van parked near McClymonds High School, a car they thought was driven by one of their intended targets. Smith says they parked, walked up to the vehicle and opened fire.

Dozens of shots rang out.

What Smith says he didn’t know was that LoEshé Lacy was also inside that van. She’d caught a ride home after finishing her part-time shift at McDonald’s, and they’d stopped to listen to music when the gunfire began. Bullets struck her in the head and the neck.

The next morning, Smith learned that he’d killed his childhood friend.

At first, Donald Lacy wasn’t above revenge.

He was getting calls from people who said they knew who killed his daughter, and they’d be happy to handle it for him. But then he remembered the example LoEshé had set months before as she dealt with her own loss.

“So I put the word out. … I don’t want any retaliation,” Lacy said. “I hadn’t forgiven at that point, but I didn’t want that sullied, negative energy on my daughter’s memory or death.”

The killing shook the city of Oakland and was front-page news in the Bay Area.

After weeks of interrogation, Smith confessed. He was 16, and was sentenced with 20 years to life.

For the next decade-plus, Lacy said, he was determined to see something positive come out of his daughter’s murder.

He stopped acting, and with a shoestring budget – including much of his own money – he started the LoveLife Foundation, an Oakland-based community organization that worked to promote non-violence through the arts and other educational programs.

He organized neighborhood anti-violence marches every year on LoEshé’s birthday, setting out from the spot where she was killed.

His work even took him to the White House, where, along with families of other victims of violence, he met with then-first lady Hillary Clinton.

But it left him little time to grieve.

“I refused to go to counseling. … Everybody in the family was devastated, and I was like, ‘I’m not going to let this break me,’” Lacy said.

It would take years, and one very public breakdown, before Lacy went to his first counseling session. That’s when he started to think about Christopher Smith.

“Once I realized what I was holding in,” Lacy said, “I realized part of the thing that was blocking me was that I hadn’t forgiven him.”

While Lacy was on the outside grappling with trauma, Smith was beginning to examine his own demons.

Because he was sentenced as a teen, he spent his first two years in juvenile hall before he was sent to two of California’s most notorious state prisons, Pelican Bay and Folsom. By 2011, Smith was in San Quentin.

Smith says that it was through group meetings in prison that he was finally able to do the work of facing the trauma of his childhood, holding himself accountable and forgiving himself.

“Embarrassingly, it was maybe until my early 30s when I really started looking into my actions and how my actions caused so much harm,” he said. “But once I had that realization and breakthrough, I felt like now I could go from being an offender to being a servant.”

He became active in a victim-offender education group, and received word that someone was interested in speaking with him.

It was Donald Lacy.

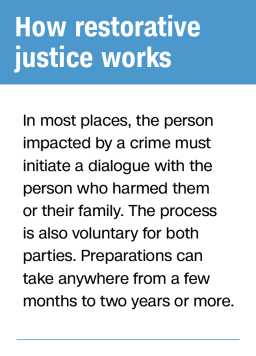

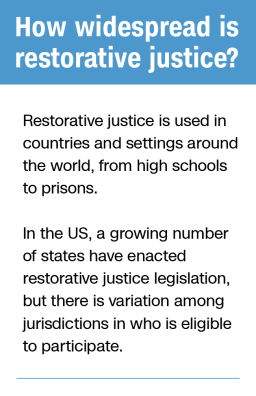

Lacy had begun working toward a meeting with Smith with the Insight Prison Project – a group that specializes in restorative justice dialogues, which are conversations that bring victims and offenders together.

Restorative justice can be applied in a variety of cases and settings, but at its core it is a process that allows both victims and offenders to have a voice, and offers both parties an opportunity to seek healing, rehabilitation and accountability. It also offers victims a chance to get answers that they may not have gotten in court.

“We’re looking at impact,” said Jonathan Scharrer, director of the Restorative Justice Project at the University of Wisconsin and an experienced restorative justice facilitator. “It’s a different focus than the traditional retributive justice lens, where the focus is just on the defendant or the person responsible for the crime.”

While some have portrayed restorative justice as a “soft” approach to violence, some advocates say they aren’t calling for an end to incarceration – just for solutions beyond locking people away.

Studies have shown that restorative justice programs can, in fact, have an impact. An analysis of several surveys on restorative justice programs around the world found that in most cases, participation in restorative justice programs reduced recidivism rates among offenders, and warrants more study.

A different approach to justice

And when given a choice, many survivors also prefer alternative responses to crime.

A national poll of crime survivors conducted by the Alliance for Safety and Justice found that 69% of those impacted by crimes preferred to hold people accountable for their actions in ways other than prison time.

It’s important, Scharrer says, not to confuse healing with forgiveness. Not every survivor wants to forgive, and it’s certainly not a prerequisite to participate in a restorative justice dialogue.

“It can be a by-product, but it’s not the focus and is not even necessarily the goal,” he said. “It happens when it happens, but there’s so much value beyond that singular thing.”

In Lacy’s case, the process of preparing to sit down with Smith to discuss LoEshé’s murder took years. He sometimes wavered on his decision to participate. Both parties had to agree to the terms and conditions around the meeting, and in the middle of the negotiations, the Insight Prison Project was approached by production company Citizen Jones.

The men were asked to participate in a new CNN series called “The Redemption Project,” and both agreed to allow cameras in the room for their meeting.

April 24, 2018.

After months of preparation, the day of their dialogue had arrived.

The pair had last seen each other two decades earlier in court, but Lacy said Smith avoided eye contact with him then.

On this day, that wouldn’t be an option. They would be sitting feet apart in a room at San Quentin prison, where Smith was incarcerated.

“I didn’t know what to expect. That fear of the unknown, the uncertainty,” Smith said. “We had prepped for the dialogue for a whole year straight, but nothing can prepare me or anyone else for a situation like that. I was nothing but raw emotions.”

Following the mediator’s lead, they each shared what they hoped to accomplish through the conversation.

As they both choked back tears, Lacy said three words that transformed both of their lives: “I forgive you.”

Smith was in shock.

“It was almost like I didn’t hear it. It’s like he had to say it a couple of times for it to really register,” he said.

Walking out of that room in San Quentin, Lacy felt “100,000 pounds lighter.”

“I’m not going to sit here and pretend that it was anywhere near easy for me to do that,” Lacy said. “But I always felt like … there’s this ancient African proverb and I forget exactly how it goes, but it’s that children choose their parents before they come into the world. I always felt like my daughter chose me for this reason.”

Six months after their meeting, Smith was paroled. Lacy had told the California courts that he was in favor of Smith’s release.

Now living back near Oakland, Smith has passed his driver’s test and received his social security card, which he never had before he went to prison. He’s also taking classes at Merritt College and working toward a degree in psychology. His goal is to become a marriage and family therapist, with a focus on single parent mothers and their children.

“I just want to put myself in a position where I can try to teach and help people to heal, whatever that may look like,” Smith said. “And in return, I’m healing in the process.”

Donald Lacy’s healing process is ongoing, too. He says he’s rooting for Smith, and wants to see him succeed in this second chance he was granted.

And for now, he wants to get back to his life, the one that was upended on that October night more than 20 years ago.

“The lesson I learned from my daughter is that we love people,” Lacy said. “This life and this world can be so much better if we just all put a little more effort into being compassionate. That was my daughter’s greatest gift.”